One of my most rewarding experiences as a soldier in the IDF was spending some of my rare moments of leisure reading John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty. The 19th century essay, which was written to discuss “the nature and limits of the power which can be legitimately exercised by society over the individual” (59), struck me as extremely illuminating and impressive. This was especially true for the second chapter of the book, “Of the Liberty of Thought and Discussion,” which, as its name suggests, is dedicated to establishing the importance of allowing complete freedom of thought and discussion (76).

|

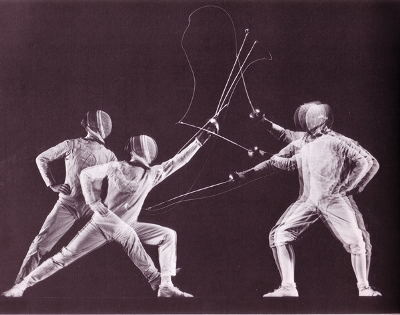

| Gjon Mili, Traceries with lights attached to foils, Ruairiglynn Museum |

Rereading the chapter closely, I find its impressive effect has to do at least partially with the way it is written. Throughout the chapter Mill simulates a conversation with his opponents, presenting the possible counterarguments that they might use against him, and then responding with attempts to refute them. I suggest that a close examination of some of these imagined discussions between Mill and his opponents indicate that the use of this dialectic style of writing serves two important objectives. Firstly, it illustrates one of Mill’s main arguments in this chapter: that even when holding an opinion that is true, in order to fully comprehend it one must continually defend it against opposition (97, 99). Secondly, this dialectic form of writing also serves as an example of the ideal, “moral” way to engage in free discussion, which Mill prescribes.

The first of these two objectives becomes apparent through close comparison between the way Mill’s first argument in the chapter is presented initially, and the way it is presented in order to refute a possible counterclaim. This comparison shows that Mill’s argument was rephrased in such a manner that reveals new aspects and consequences that were not originally apparent. The fact that this rephrasing occurs as part of the attempt to refute the counterargument seems to illustrate Mill’s notion that only through repeatedly attempting to rebut opposing views can one gain better understanding of one's own opinion. At first, Mill presents the argument thus:

To refuse a hearing to an opinion because they [i.e. those who refuse its hearing] are sure that it is false is to assume that their certainty is the same thing as absolute certainty. All silencing of discussion is an assumption of infallibility. Its condemnation may be allowed to rest on this common argument, not the worse for being common. (77, emphasis in original)

After discussing this argument in further detail (77-78), Mill introduces a possible counterclaim:

The objection likely to be made to this argument would probably take some such form as the following. There is no greater assumption of infallibility in forbidding the propagation of error than in any other thing which is done by public authority on its own judgment and responsibility. Judgment is given to men that they may use it. Because it may be used erroneously, are men to be told that they ought not to use it at all? (78)

Having presented this counterclaim, Mill attempts to rebut it:

There is the greatest difference between presuming an opinion to be true because, with every opportunity for contesting it, it has not been refuted, and assuming its truth for the purpose of not permitting its refutation. Complete liberty of contradicting and disproving our opinion is the very condition which justifies us in assuming its truth for purposes of action; and on no other terms can a being with human faculties have any rational assurance of being right. (79)

As can be seen, in his attempt to refute the counterclaim, Mill modifies and expands his original argument. The original argument focused on the opposing opinion, explaining that doubt regarding its falseness should secure it from being silenced. Following the introduction of an opposing view, the same argument is now presented from a different perspective, focusing on doubt about one’s own opinion being true. Furthermore, this new perspective allows a new consequence of the argument to be realized. The consideration of the fallibility of one’s own views leads to the conclusion that the only precondition that allows one to have sufficient “rational assurance of being right” is that of complete freedom on the part of others to offer objections and contradictions (Ibid.). Thus, Mill presents the rephrasing of his argument, which reveals new aspects and consequences of it, as a direct result of his attempt to defend it against opposition. Through this simulation of free discussion Mill illustrates the illuminating effect he claims it has on the understanding of one’s own opinion (99).

This dialectic pattern continues throughout the chapter. It occurs, for example, after Mill gives voice to another counterclaim to the argument mentioned previously. According to this claim, silencing opinions is justified because truth can never be fully suppressed and will always come out in the long run, while “persecution” may be effective against “mischievous errors” (87-88). Mill gives a very lengthy response to this argument, his final point being:

Those in whose eyes this reticence on the part of heretics is no evil should consider […] it is not the minds of heretics that are deteriorated most by the ban placed on all inquiry which does not end in the orthodox conclusions. The greatest harm done is to those who are not heretics, and whose whole mental development is cramped and their reason cowed by the fear of heresy […] there never has been, nor ever will be, in that atmosphere an intellectually active people. (95)

Mill takes the argument further, claiming that only during the periods that were free from this suppressive “atmosphere” did humanity experience any progress (96). Thus, Mill sheds new light on his original argument and claims a new consequence deriving from it. After claiming that free expression of opinion is needed to prevent the silencing of truth (76-77), and then emphasizing that it is a precondition for assuming one’s individual opinion to be true (79), he now claims that is a necessary prerequisite for the progress of humanity (96). As can be seen, this is another example of the fact that the realization of new aspects and consequences of Mill’s arguments in this chapter is often presented as the outcome of an attempt to refute an opposing opinion. It may be observed, therefore, that by presenting the development of his arguments in this manner, Mill is able to use his dialectic style of writing to illustrate one of the main benefits he attributes to free discussion.

The dialectic pattern is also apparent in the chapter’s conclusion. After summarizing the main arguments in defense of free discussion demonstrated in the chapter (115-116), Mill once again gives voice to opposition:

Before quitting the subject of freedom of opinion, it is fit to take some notice of those who say that the free expression of all opinions should be permitted on the condition that the manner be temperate, and do not pass the bounds of fair discussion. (116)

Although Mill disagrees with the notion that such limits should be imposed “by law and authority” (118), he does acknowledge the importance of civil discourse, and uses the opportunity to describe his view of the “morality of public discussion”:

[…] giving merited honour to everyone, whatever opinion he may hold, who has calmness to see and honesty to state what his opponents and their opinions really are, exaggerating nothing to their discredit, keeping nothing back which tells, or can be supposed to tell, in their favour. (Ibid.)

This ideal of the “morality of discussion”, according to which one takes care to give due notice and credit to one’s opponents, explicitly stating their possible arguments, in effect describes the way the chapter itself is written, as can be seen in the examples above. It may be argued, therefore, that another function of the chapter’s style of writing is to act as a model for Mill’s view of the proper way one should engage in a free discussion.

Analyzing the way this chapter is written, in which “[the] opponents and their opinions” (118) are constantly taken into account, and their supposed arguments are presented and debated, may lead to the observation made above: that this form of writing was intended to have at least two major effects. On one level, the fact that the reader gains deeper and fuller understanding of Mill’s arguments by being exposed to opposing opinions and the attempts to refute them serves to simulate the unique effect Mill attributes to free discussion – gaining fuller realization of the truth. On another level, this form of writing, which presents an argument that attempts to voice possible objections that it might face, appears also to serve as a model for the way Mill believes free discussion should be conducted. Reading the chapter and encountering this dual process, through which what is argued is also reflected by the style, can leave a lasting impression.

Considering that often today little importance is placed on style and language, and that rhetoric is often considered to be synonymous with populism, Mill’s impressive demonstration of both the power of style to clarify and convince, and the ability to put this power to honest and responsible use, may seem as inspiring and illuminating as the ideals it was used to convey.

Bibliography:

- Mill, John Stuart. On Liberty, 1859, London: Penguin Books Ltd., 1985.

0 תגובות:

Give us a piece of your mind